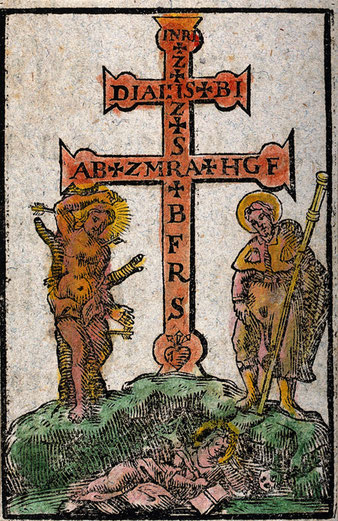

17th-century plague amulet, with three saints who just might help protect against illness and infection: Sebastian, Roch, and John of Nepomuk. (Social distancing is probably more effective.)

I love that John (who was Vicar General of Prague, a city I have a deep bond with) is reading.

I was born in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The day my mother was labouring to launch yours truly into the world, October 18, 1962, US president John F. Kennedy was meeting with the foreign minister of the Soviet Union, Andrei Gromyko, to inquire of him why the hell the Russians were putting missiles in Cuba, within striking distance of the United States. Here they are in the Oval Office on my birth day:

Gromyko (uncharacteristically almost smiling here) was a fixture of my childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. This dour gentleman, a bit like a grave and mysteriously menacing teddy bear, was supposed to be the person who would deliver the news that we were about to be obliterated.

I have vivid memories of one summer, perhaps 1979 or 1980, when I was firmly and quietly convinced the world was about to end. The Cold War and arms race was in the news every day, Gromyko was still the Soviet foreign minister, and peace activists were going around chalking the outlines of bodies onto sidewalks to simulate what we’d be reduced to when the missiles struck. This was happening even in my hometown of Belleville, Ontario. If the Soviets could hit us there, on Cedar Street or at Queen Mary School or in Centennial Park, they could hit anyone, anywhere.

At a time when I was nearing the end of my high school years and might otherwise have been considering what to “do with my life,” I had a deep conviction that I didn’t really need to think more than six months ahead, because we were all doomed anyway.

All of which is to say that I know something about existential anxiety. It’s

basically been the background of my life. I was born into it and grew up with

it. I would agree with Kierkegaard, Sartre and Co. that anxiety is the state we

all live in, although some people, at some times, are more aware of it.

Of course, what we’re dealing with now is very real. People are dying. But there are similarities between the situation in Canada at this time—3:42 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time on March 18, 2020—and the anxiety I was born into and grew up with. These past few days (less than a week, amazingly, since our consciousness was raised), the problem for most of us in Canada isn’t so much what’s actually happening as fear of what might, or could, or will probably, happen (read: Italy).

Joseph Campbell said we should strive to achieve a state of mind in which everything becomes a symbol.

So, what would this worldwide pandemic be a symbol of?

Unlike the recurring Cold War crises, this doesn’t come down to human stupidity and aggression. Put your differences aside and love one another just won’t cut it this time as the main takeaway.

This pandemic is showing us, I think, how fragile everything is: our way of life, our neighbourhoods, our lives. Everything we take for granted.

For all our wisdom and technology, we don’t control much.

So, symbol #1: Fragility.

And symbol #2: Physicality. Our bodies live (and will die) in physical, not

virtual, space. However rich our virtual lives, it is the physical world we

live in, interact with, play with, suffer from, and (to a certain extent) affect.

So, bearing these symbols in mind, this could be a wonderful opportunity to see our world differently, to grow spiritually, to ask ourselves what gives real meaning to our fragile physical lives.

As for what gives meaning, I won’t suggest anything. At least not right now. (Maybe that will be for next time.) This looks like being a long-drawn-out symphony, with ample space between and within the various movements for each of us to take time to reflect.

Take care of yourselves.

Write a comment